When I first moved back to Newcastle, a local organisation did a competition based on Geordie dialect and phrases that were slipping into disuse. I can’t remember if I ever entered it – it got cancelled due to Covid, if I recall – but I did write something, in part based on my own experience, and the sheer, delighted buzz I got the first time I heard the words of my past from the mouths of teens on the Metro. Anyway, I was doing some life admin yesterday and found what I’d written and then filed away and forgotten, so thought it would be fun to share. Do let me know if I’ve included any of your favourite memory words – or the ones that you would have included!

Wrap These Words Around You Like a Scarf to Keep You Warm

(A Short Story by Tracey Sinclair)

The words land like blows, or the sharp tug of a sleeve caught on a door she’d already walked through, pulling her back into a room she just left.

“He’s geet lush, man! Eeee, look at him! Pure mint!”

Caron looks over at the source of the high-pitched squeal, a gaggle of girls leaning into each other in the four-seat booth of the Metro. A pretty teen in a brightly coloured hijab, lashes as generous as a goat’s, laughing as she taps her phone with the tips of elaborate nails, sharing something with her friends that elicits a fresh round of glee. One of her mates is lanky and blonde, pale as a peeled potato – ‘peelly wally’, the phrase bobs unbidden into Caron’s head in her mother’s voice, but maybe that’s a look now, she’s been away too long to know. The other is plump with the regal poise of a ringleader, face as painted as an Old Master, framed by ironed-flat hair and geometric eyebrows, her true complexion only visible through the deliberate rips in her packed-tight skinny jeans.

“Gis a deek, then,” she demands, pulling the phone for a closer look, and they tussle for control of the screen, a shoving match that turns into an opportunity for a selfie, and the three of them push and play and joke, oblivious to the attention they are getting from the rest of the carriage, censorious or curious, depending on the gender and age of the onlooker. Caron feels a surge of pure affection, so visceral she has to look away. The words, the accent, they feel like an echo, her own past rising to welcome her home. She can’t remember the last time she felt so included.

Face turned to the window, scenery blurs into memory. A boy she thought was mint, lush, a proper belta – all those words and more that she never uses now. 15 years old, the pair of them, clueless and besotted and more innocent than she could now believe possible. Courting, her parents said they were, though she didn’t understand that antiquated phrase any more than she comprehends its modern equivalents (dating? hooking up?) with all the US-imported vagueness they seem to entail. Maybe that’s why she’s so bad at it.

Going out, they called it. Seeing each other. And they saw each other plenty, though beyond the obvious teenage fumbles she can’t recall how they managed to so completely fill up one another’s time. Knocking round the houses, hanging around bus stops with his mates, divvying up tabs nicked from his dad’s sideboard, knocking back cheap cider, bottles of dog and alcopops. Occasionally just the two of them, snogging on the gravestones at the cemetery near the bus station because they were both into The Smiths and thought it was romantic.

Her parents tolerated their infatuation. Maybe even liked him, though her dad was baffled by the appeal of his Morrissey hair and his paisley shirt, jeans rolled up over second-hand Doc Martens (‘pit boots’, the family called them, her mother up a height when Caron bought a pair for herself.) ‘He’s a canny lad, but the clip of him,’ her dad moaned, but her mum – Mam, back then – was sharp-eyed enough to see it was serious.

They were allowed in Caron’s room (her doorplate spelling Karen, the too-tainted, now-discarded version of her name).

“Don’t know how you can relax in that midden,” her mum would tut at the discarded vinyl LPs scattered on the floor, posters Blu-tacked on the walls Caron was cruelly forbidden from painting black. Clearly, her mum worried that relaxing wasn’t all they were up to; the door was left an inch open, and she cheerfully arrived bearing trays of Dandelion and Burdock and stottie sarnies if she thought things had gone too quiet.

It was Caron’s gran who sounded warning. Door on the sneck – a habit no amount of watching Crimewatch could deter her from – her house was a haven, where she would make them some bait or send them off with black bullets (Caron thinks, wryly, that telling her London friends she had too much ket and bullets as a child would raise a degree of alarm). But for all her apple-faced openness, the woman had a gimlet eye. “Gan canny with that one,” she warned. “He dresses like your wan off the telly, but deep down he’s soft as clarts.”

She hadn’t been wrong, had she? It was him who cried, when London called and Caron answered. Him who offered to pack in his apprenticeship and come with her, while she just shook off him and the city, the desperation for novelty making her cruel. He was married now, Caron knew from some light social media stalking, two kids and a wife in Washington Village, doing something impressively senior over at Nissan. She hoped he was happy, that staying had got him what leaving didn’t get her.

“Ah, man! Delete that! I look pallatic, my dad’ll gan radgie!”

The girls are laughing again. Caron’s surprised by the sharpness of their accents, the specificity of their words. She thought everyone sounded like the internet now, homogenous and with bad grammar. It’s a shock to hear the region embedded in their speech, as clearly as it had once been in hers. She thinks about her own accent, smoothed by the south and the incomprehension of strangers, familiar words abandoned like unwanted baggage, for fear of being weighed down. She thinks of the man she left in London; no tears at that parting. Was some of their indifference that he never really knew her; there was nothing real for him to miss? If you shape and shear yourself down to a sliver, a spelk, to fit the expectations of others, what is left of you?

She’d been wondering what had drawn her back, after so many years of rare, sporadic visits and much-postponed trips and the ever-accepted London lie of “working”. Why this latest break up, the last in a long line, has sent her careening home. And she realises, suddenly, a recognition as clear as the accents around her, that what she has finally come looking for is the sound of her own voice.

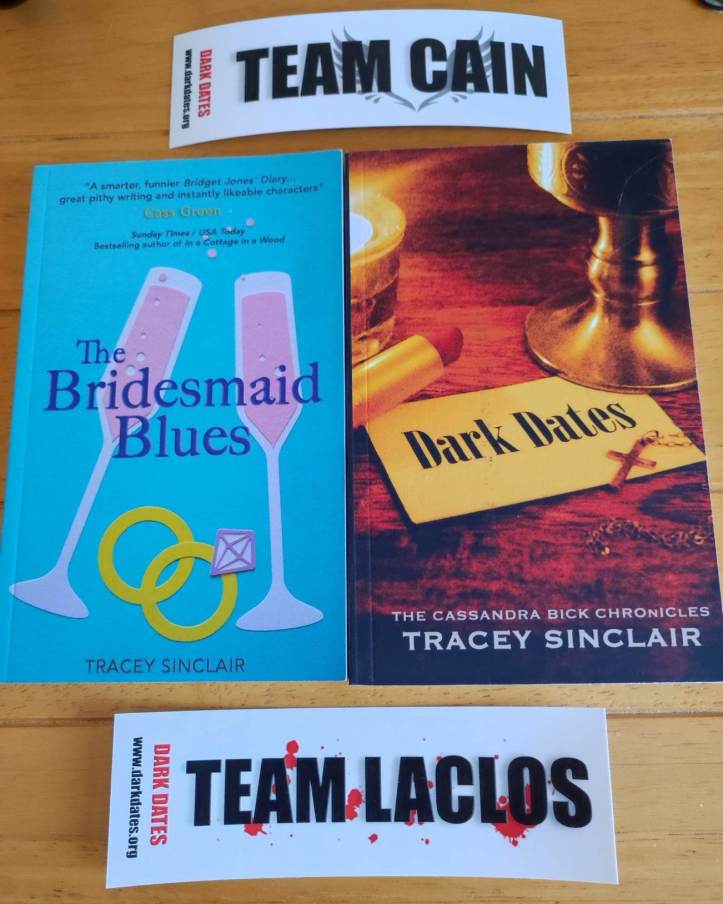

Remember, if you like my writing you can support me by buying me a Ko-fi or buying one of my books – if you want something set in Newcastle, there is Bridesmaid Blues, or all of my Dark Dates novels are currently only 99p on Kindle. And if you want more Tracey in your inbox – how could you NOT? – sign up to my free Substack. Trust me, even the smallest gesture of support is welcome!